The development and spread of antimicrobial resistance is an ongoing global phenomenon that predates the introduction of the first antibiotics to the market. Unfortunately, the anthropic impact on bacterial communities has led to this process being accelerated and we experience a reduction in the efficacy of our therapeutic arsenal and an increase in the incidence of resistant bacterial infections.

Table of Contents

Why do we not produce new antibiotics?

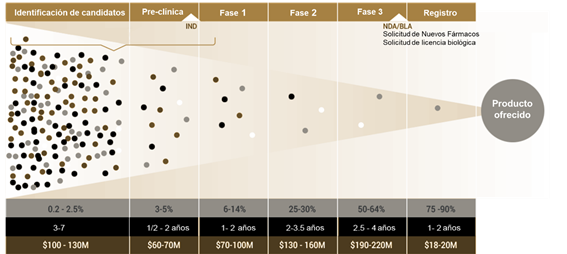

The development of new chemical entities towards drugs is increasingly difficult and expensive. It is estimated that to introduce a new antibiotic to the market requires an investment of more than 500 million dollars, although some authors estimate a budget greater than 1.58 billion dollars, not including post-launch studies.

Developing new antibiotics is not a financially appropriate decision for investors, even less when it comes to compounds from a new family, which have a lower probability of success and greater uncertainty regarding their toxicity and physicochemical properties.

Another point to consider is that nothing would prevent certain pre-existing genetic determinants in the microbial pangenome from being selected through the new selective pressure and rapidly evolving into effective antimicrobial resistance against these new substances.

Are we entering the post-antibiotic era?

The scenario is gloomy and it seems that this statement is becoming more and more certain. However, the development of science-based strategies has allowed us to detect new tactics to combat the problem of antimicrobial resistance. One of them is to take advantage of drug interactions in favor of our specific objectives through antibacterial associations.

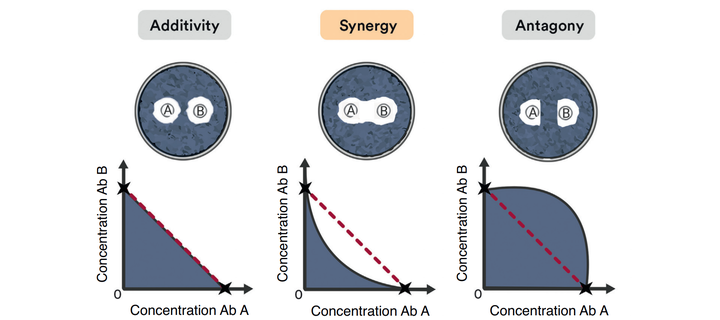

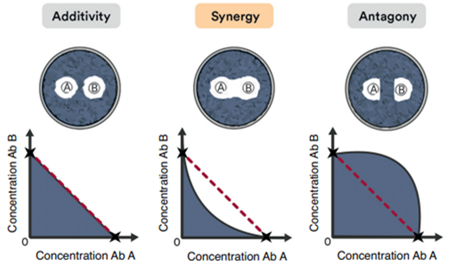

There are 3 types of drug interactions depending on the variation in the bactericidal effect of drugs:

- Additive: The effect of antibiotics is summative

- Synergistic: The effect of antibiotics is greater than the sum of both drugs

- Antagonic: Antibiotics interfere with each other and their effect is compromised

Importance of antimicrobial associations

From a clinical point of view, synergistic interactions stand out from the rest by achieving a combined effect greater than the sum of the individual activity of each drug. This means that it is possible to reduce its dose and toxicity while maintaining the benefits and the increased therapeutic effect of the association.

Other advantages of synergistic interactions between antibiotics is the broadening of their bactericidal spectrum, which offers better coverage in treatment when the etiology of the infection is unknown. Several studies also claim to reduce the emergence of antimicrobial resistance by reducing the probability of relapse and allowing the rescue of “old” or “obsolete” antibiotics so that they can be reused effectively and with even a better prognosis than currently available monotherapies.

The synergistic effect of these substances can occur through various mechanisms, such as: parallel inhibition of metabolic pathways, mutual stabilization of the binding site, sequential blocking of the same pathway (in order to avoid biological redundancies and reduce the final phenotype), modulation of bioavailability and inhibition of inhibitors. This advance in pharmacology opens up a promising field of research that needs to be explored in greater detail.

Antibacterial Associations in Veterinary Medicine

In the field of veterinary medicine there are antibacterial associations that have already proven their effectiveness in different settings and situations. One of these is the association amoxicillin and enrofloxacin, both molecules have a bactericidal effect against gram positive and gram negative bacteria, but they act under different mechanisms of action.

Amoxicillin, like other b-lactams, inhibits the last phases of the synthesis of the cell membrane of bacteria through its union with penicillin-binding proteins and increases its permeability by acting as a blocker of open channels of OmpF. Enrofloxacin, for its part, is an inhibitor of bacterial topoisomerases II and IV (Girasa and Topo IV), enzymes necessary for the supercoiling and synthesis of DNA in these organisms.

The synergistic effect of the association amoxicillin and enrofloxacin is mediated by the principle of modulation of bioavailability; a powerful combination that allows treating both simple and complex infections in a wide variety of tissues and fluids due to the large volume of distribution and tissue penetration of both drugs, as well as their good post-antibiotic effect.

To learn more antimicrobial associations approved for use in animals, you can review our catalog here.

If you liked this article, share it and write to us if you have any questions. Until next time!

References

- D’Costa, V. M., King, C. E., Kalan, L., Morar, M., Sung, W. W. L., Schwarz, C., Wright, G. D. (2011). Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature, 477(7365), 457–461

- Phylogenetic analysis shows that the OXA beta-lactamase genes have been on plasmids for millions of years. Barlow M, Hall BG J Mol Evol. 2002 Sep; 55(3):314-21.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance.

- Mazzaferro EM: Triage and approach to the acute abdomen. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 18:1–6, 2003.

- Mazzaferro, E. M., (2004), Critical Care for HeatInduced Illness, International Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Symposium 2004

- Sullivan et al. 2020. How antibiotics work together: molecular mechanisms behind combination therapy. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 57, 31-40.

- Pillai SK, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos GM. In: Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine. Lorian V, editor. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2005. pp. 365–440

- Nedbalcova K., Zouharova M., Sperling D. (2019): Post-antibiotic effect of marbofloxacin, enrofloxacin and amoxicillin against selected respiratory pathogens of pigs. Veterinarni Medicina, 64: 67-77.

- Horowitz JB, Moehring HB. How property rights and patents affect antibiotic resistance. Health Economics. 2004 2004/06/01;13(6):575-583.

- Mouton, J. W. (1999). Combination therapy as a tool to prevent emergence of bacterial resistance. Infection, 27(S2), S24–S28. doi:10.1007/bf02561666